On the Origins and Functions of the Roman Senate and Magistracy

On the Origins and Functions of the Roman Senate and Magistracy

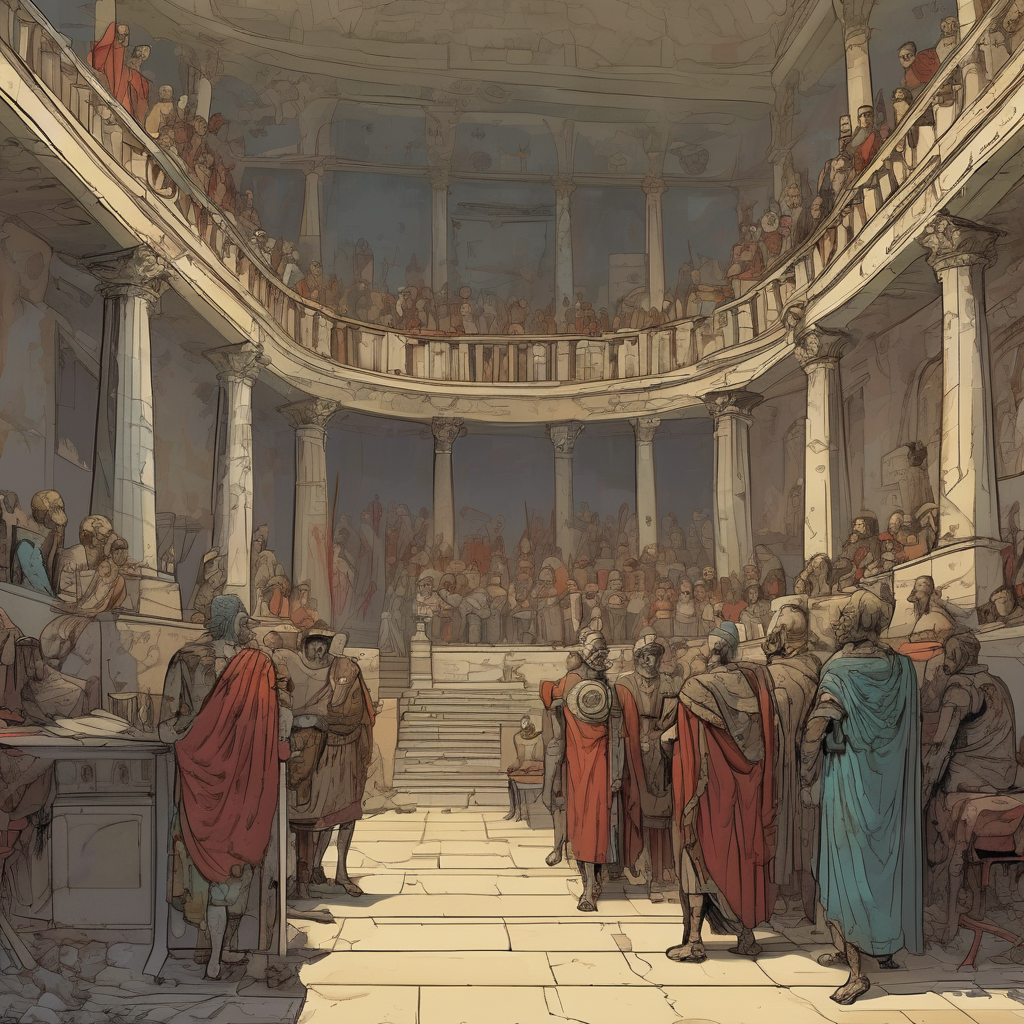

Behold, the Roman Senate, that venerable institution, traces its origins to the earliest days of our great city, a foundation laid in the year of our city’s birth, 753 BCE. It is said that Romulus, our illustrious first king, established the Senate as a council of wise elders—or patres—who would advise him in the governance of the realm. In those early days of monarchy, the Senate held a vital advisory role, yet it lacked the power to enact laws in its own right.

With the expulsion of the last king, Tarquin the Proud, in 509 BCE, Rome embraced the ideals of the Republic. In this new political order, the Senate emerged as a central pillar of governance, entrusted with advising elected magistrates, overseeing public finances, and steering the course of foreign policy. It was within this framework that the Senate’s influence flourished, guiding the Republic through its many trials.

The Magistrates of Rome

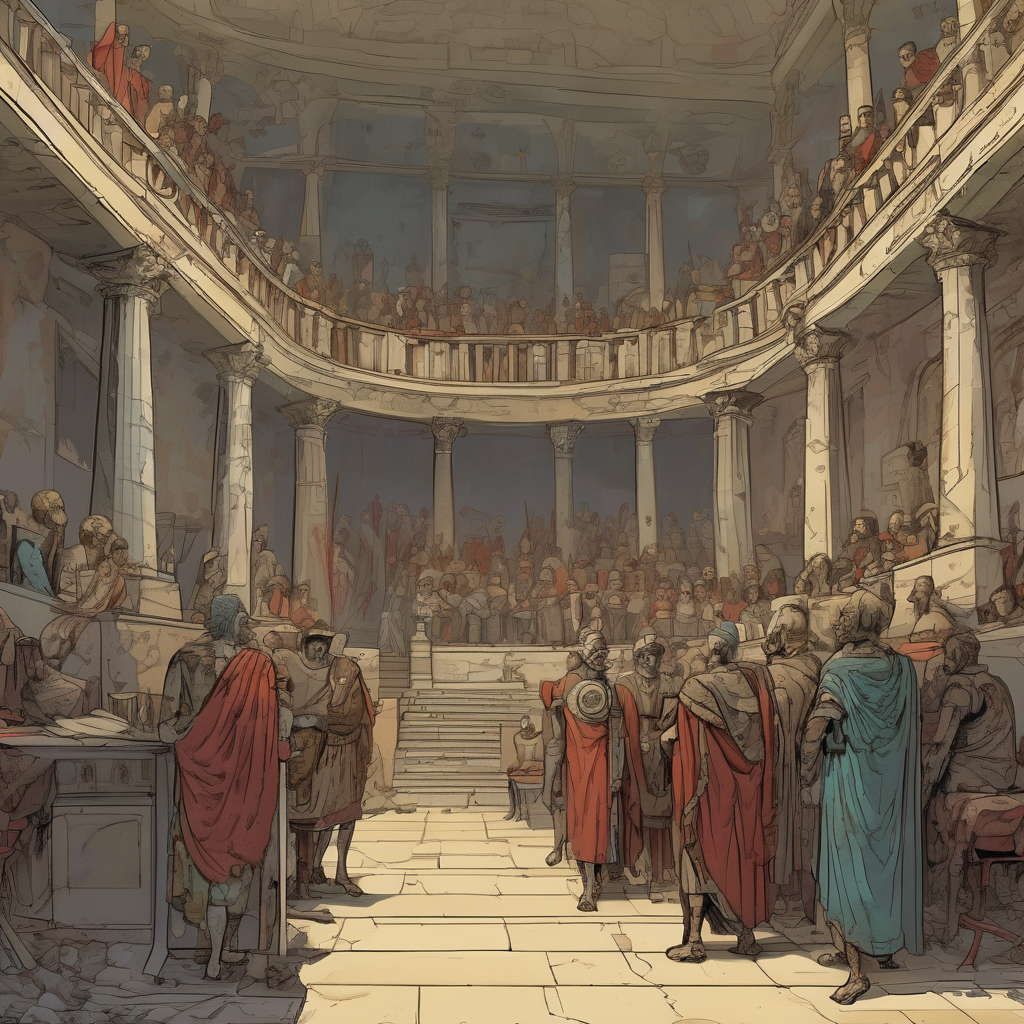

In ancient Rome, the magistrates stood as elected officials endowed with both administrative and judicial powers, forming the backbone of governance in both Republic and Empire. Let us examine the hierarchy of these magistrates:

Consuls: The highest officials of the Republic, the consuls commanded the military and presided over the Senate. Elected annually, there were typically two, ensuring that power was not concentrated in a single individual.

Praetors: Serving primarily as judges, praetors wielded significant authority in matters of law. They could also command armies and govern provinces, with distinct roles such as the Praetor Urbanus, who managed legal affairs among citizens, and the Praetor Peregrinus, who dealt with matters involving foreigners.

Aediles: Tasked with maintaining public buildings, organizing games and festivals, and regulating markets, aediles ensured the smooth functioning of urban life. There existed two types: Plebeian Aediles, elected by the common people, and Curule Aediles, often from the patrician class, wielding greater prestige.

Quaestors: These financial officers managed the state’s treasury and public funds. Serving under higher magistrates, they often embarked upon their political careers as the initial step in the esteemed Cursus Honorum.

Censors: Elected every five years, the censors conducted the census and oversaw public morals and contracts, wielding considerable power during their limited term.

Tribunes of the Plebs: Elected to represent the common people, these tribunes possessed the extraordinary power to veto decisions made by other magistrates, thereby safeguarding the rights and interests of the plebeians.

The Cursus Honorum

The path of political progression, known as the Cursus Honorum, delineated the sequence of public offices held by aspiring leaders. Aediles, praetors, and consuls formed the core of this noble journey, each office a stepping stone toward greater authority and responsibility.

Aediles were tasked with the upkeep of public structures and the organization of civic festivities, ensuring that the lifeblood of the city thrived.

Praetors, the custodians of justice, managed legal disputes and commanded armies, serving as the backbone of Roman law and governance.

Consuls, the apex of Roman authority, commanded the military, presided over the Senate, and represented the Republic in foreign affairs. Their dual election served to prevent the accumulation of power in any one individual, embodying the principles of checks and balances.

The Role of Tribunes

Initially, the office of the Tribune of the Plebs was established with two representatives in 494 BCE, designed to protect the interests of the plebeians against patrician dominance. This number gradually swelled to ten, reflecting the increasing complexity of our political landscape. The tribunes, elected annually by the Plebeian Council, became crucial defenders of the common people, wielding the power of veto and convening assemblies to pass laws.

The late Republic was a tumultuous era, marked by factional strife among populists, optimates, and ambitious military leaders. Amidst this chaos, the influence of the Tribunes of the Plebs waxed and waned, often entangled in the broader political conflicts of the day.

Transition to Empire

The culmination of these struggles led to the transition from Republic to Empire, epitomized by Augustus (Octavian), who became the first emperor in 27 BCE. In this new order, the Senate’s power diminished, while the authority of the emperor rose.

The Concept of Sacrosanctity

A notable aspect of the tribunes’ power lay in their sacrosanctity—a principle that rendered them inviolable. Harming a tribune was deemed a grievous offense, reinforcing their role as protectors of the plebeians. This notion of inviolability not only elevated the tribunes’ status but also highlighted their imperative duty to advocate for the common people.

In this light, the tribunes adorned themselves with insignia to signify their sacred status, visually representing their authority and the protection afforded to them. Yet, this very protection also sparked tensions, as the tribunes faced violence and threats—most notably exemplified by the tragic fate of Tiberius Gracchus, who was slain in his quest for reform.

Thus, the sacrosanctity of the Tribunes of the Plebs not only empowered them to champion the interests of the populace but also laid the groundwork for contemporary understandings of political protection and representation. In reflecting upon this legacy, we recognize the importance of safeguarding those who represent the voice of the people, a principle that resonates through the annals of history.

Comments

Post a Comment